I really hate to see girls going to tanning beds. I even get nervous when I see people lay out in the sun without sunscreen on. Yes, yes, I know- the warmth feels so nice and you look like you belong in a Ralph Lauren magazine ad afterwards. That’s just a misleading coincidence, though. A tan is literally the observable result of directly damaging your skin via radiation. Won’t be so cute when you’re only 30 and your chin skin is already drooping, you have brown spots all over, and wrinkles you shouldn’t have until you’re 50.

|

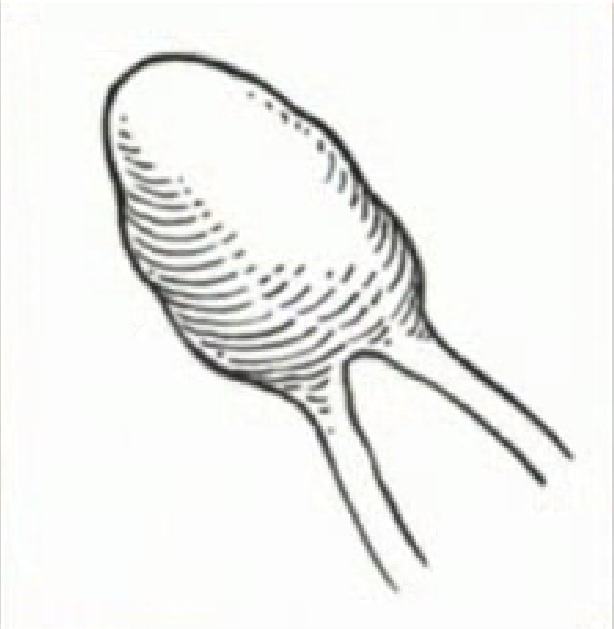

| Big brown blotch is a melanocyte releasing melanin into the skin. |

Melanin is the brown/black pigment in your skin, and is made and released by cells called melanocytes. Everyone has melanin (except albinos), although the amount of melanin people produce varies. Interestingly enough, it has been found that everyone, no matter ethnicity, has the about the same amount of melanocytes. What determines skin color is DNA, and whether it tells them to make melanin or not. Black and Indian people’s melanocytes tend to produce more than Viking-type folk, so they appear darker.

Melanin exists in your skin to help absorb the ultraviolet radiation you get from the sun. UV radiation literally bursts your melanocytes (sounds violent, doesn’t it? Yeah. It’s not good. Stop going to the tanning bed.) so that melanin is released into the skin to act as a sort of protective blanket for your dermal tissues. That tan and glowy girl working in American Eagle is really wearing one big skin Band-aid.

Back in 1986, there was an explosion and subsequent fire at a nuclear power plant in Ukraine. The fire caused a radioactive gas to float across an extensive landscape and into the atmosphere, sending civilians into a panic and mass exodus. The radiation wiped out life in the area. Birds, fish, mammals, bugs, you name it. And what didn’t receive lethal amounts of radiation and survived was still radioactive. Nothing thrived in this environment… until recently.

In 2006, Chernobyl research robots found a curious black fungus crawling on the walls of old reactor. Samples were taken and it was found that it had an enormous concentration of melanin. This fungus had adapted to the radioactive environment via high melanin production. While it does not “de-radioactivate” the radiation, it sort of stores it as a means of energy acquisition.

Researchers have conjectured that this may be a means of energy production in the future. Since the fungus is harnessing energy, maybe it could be eaten as an energy-rich food. Or maybe astronauts could use it to absorb the excess radiation they’re continually exposed to. I’m sure we’ll see something come of this in the future.

I, however, point out that if melanin is produced in a black crawling fungus in Chernobyl to absorb leftover radiation, it exists in us for similar reasons. The difference is, we cannot capture the energy in a beneficial way like the fungus. Instead, radiation causes the breakdown of skin elasticity and the increased likelihood of cancer. This being said, let me clarify that moderate sun-exposure is in no way comparable to the radiation at Chernobyl. But this little melanin story should get you thinking. Your skin reacts to the tanning bed in same way that this fungus has reacted to nuclear radiation… increased melanin production.

|

| Please. |